Table of Contents

RDoc

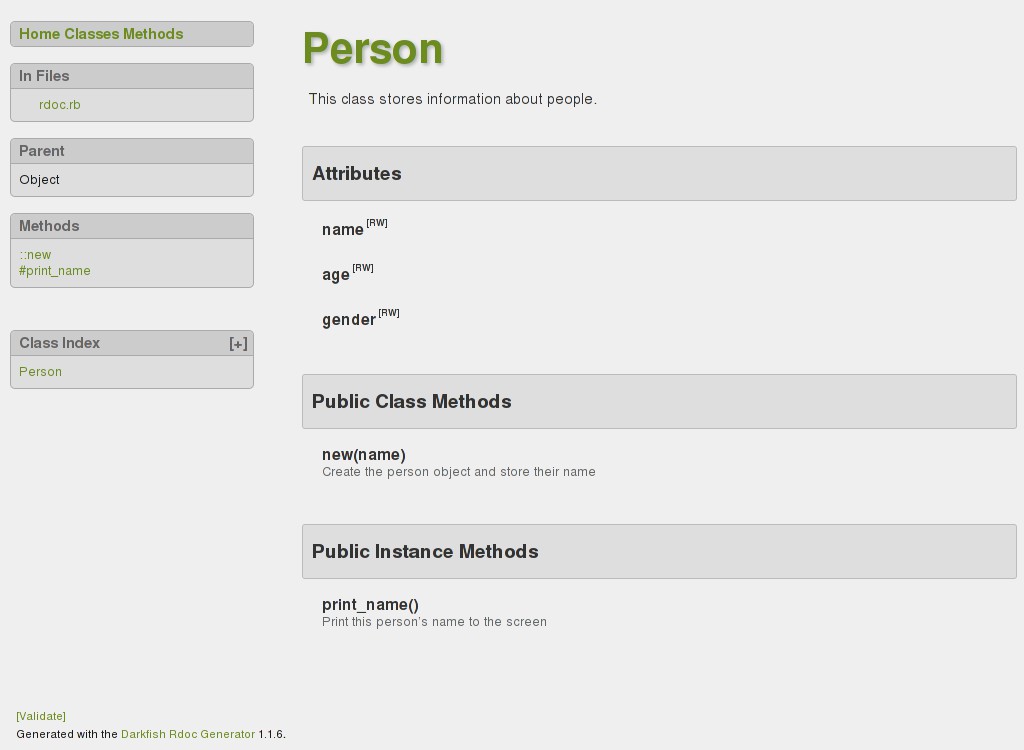

- RDoc - narzedzie, ktore przeglada pliki zrodlowe Rubiego, i na ich podstawie generuje dokumentacje HTML. Podobnie jak w przypadku phpdoc, konieczne jest stosowanie sie do pewnych form komentarzy.

# rdoc.rb # This class stores information about people. class Person attr_accessor :name, :age, :gender # Create the person object and store their name def initialize(name) @name = name end # Print this person's name to the screen def print_name puts "Person called #{@name}" end end

Uruchamiamy RDoca:

sqbell@sqbell-gentoo ~/ruby/beginning_ruby/ch08_doctestdebug.rb $ rdoc rdoc.rb Parsing sources... 100% [ 1/ 1] rdoc.rb Generating Darkfish... Files: 1 Classes: 1 ( 0 undocumented) Constants: 0 ( 0 undocumented) Modules: 0 ( 0 undocumented) Methods: 2 ( 0 undocumented) 100.00% documented Elapsed: 0.0s

sqbell@sqbell-gentoo ~/ruby/beginning_ruby/ch08_doctestdebug.rb $ ls -la doc/ razem 44 drwxr-xr-x 2 sqbell sqbell 4096 05-05 17:35 . drwxr-xr-x 3 sqbell sqbell 4096 05-05 17:35 .. -rw-r--r-- 1 sqbell sqbell 6726 05-05 17:35 Person.html -rw-r--r-- 1 sqbell sqbell 72 05-05 17:35 created.rid -rw-r--r-- 1 sqbell sqbell 1459 05-05 17:35 index.html -rw-r--r-- 1 sqbell sqbell 12560 05-05 17:35 rdoc.css -rw-r--r-- 1 sqbell sqbell 1240 05-05 17:35 rdoc_rb.html

Bardzo ladnie to wyglada. ![]()

- Zeby RDoc cos zignorowal, korzystamy z modyfikatora

:nodoc:po definicji modulu, klasy czy metody:

def secret_method #:nodoc: end

- Jesli chcemy, aby

:nodoc:obowiazywal od wystapienia do wszystkiego ponizej (ale wewnatrz), na przyklad aby wszystkie metody ponizej byly ukrywane, korzystamy z:nodoc: all. Jesli inna klasa bedzie zdefiniowana ponizej, bedzie ona dolaczona do dokumentacji. - Jesli nie chcemy, by czesc komentarzy byla przetwarzana przez RDoca, korzystamy z

#++i#--:

# I think that John is pretty #-- # stupid fella. #++ # and I really like him.

- RDoc nie przetwarza komentarzy wewnatrz metod.

- Za pomoca opcji linii komend, mozna wyeksportowac dokumentacje do roznych formatow (xml, yaml, chm, pdf):

–fmt <format name>

Obsługa błędów

# exceptions_01.rb class Person def initialize(name) raise ArgumentError, "No name present!" if name.empty? end end fred = Person.new('')

Output:

exceptions_01.rb:5:in `initialize': No name present! (ArgumentError) from exceptions_01.rb:9:in `new' from exceptions_01.rb:9:in `<main>'

- Mozna tworzyc wlasne wyjatki. Robi sie to gdyz, dzieki temu mozna roznie radzic sobie z roznymi wyjatkami.

- Wyjatki obsluguje sie za pomoca slowa

rescue(orazbeginiend):

# exceptions_02.rb begin puts 10 / 0 rescue puts "You caused an error!" end

- Podobnie obsluguje sie kilka wyjatkow:

# exceptions_03_ps.rb begin #code here rescue ZeroDivisionError #code here rescue YourOwnException #code here rescue #code that rescues all other types of exception end

- Poza obslugiwaniem, mozna tez otrzymywac wyjatki i ich uzywac:

# exceptions_04.rb begin puts 10 / 0 rescue => e puts e.class puts e.backtrace end

Output:

ZeroDivisionError exceptions_04.rb:4:in `/' exceptions_04.rb:4:in `<main>'

Catch i Throw

- Czasem fajnie by bylo moc przerwac wykonywanie jakiejs, na przyklad, petli podczas normalnej pracy w podobny sposob jak dzieje sie to z wyjatkami, ale bez faktycznego generowania bledu. Do tego wlasnie przydaja sie

catchithrow. - Dzialaja z symbolami a nie z wyjatkami.

# catch_throw_2.rb def generate_random_number_except_123 x = rand(1000) throw :finish if x == 123 end catch(:finish) do 1000.times { generate_random_number_except_123 } puts "Generated..." end

Debugger

- debuggera uruchamiamy za pomoca polecenia

ruby -r debug debugfile.rb. To przeniesie nas do konsoli podobnej doirb:

Debug.rb Emacs support available. debugtest.rb:3:i = 1 (rdb:1)

- Za pomoca specjalnych polecen, mozna wykonywac program linia po linii, lub ustawic szereg breakpointow.

- Polecenie

listwyswietla linie programu, nad ktorymi aktualnie pracuje:

(rdb:1) list [-2, 7] in debugtest.rb 1 # debugtest.rb 2 => 3 i = 1 4 j = 0 5 6 until i > 1000000 7 i *= 2

stepprzechodzi do nastepnej linii programu,contwykonuje caly program bez krokow,breakustawia breakpoint w pewnej linii:break 3ustawia breakpoint na linii 3,watchustawia warunkowy breakpoint, zamiast linii wykorzystujemy tu jakis warunek:watch x > 10,quitwychodzi z debuggera,- wpisujac nazwe zmiennej, wyswietlamy jej zawartosc.

Testowanie

- Test-driven development - najpierw testy, pozniej kod, iteracyjnie.

# testing.rb class String def titleize self.gsub(/\b\w/) { |letter| letter.upcase } end end raise "Fail 1" unless "this is a test".titleize == "This Is A Test" raise "Fail 2" unless "another test 1234".titleize == "Another Test 1234" raise "Fail 3" unless "We're testing titleize".titleize == "We're Testing Titleize"

Output:

testing.rb:11:in `<main>': Fail 3 (RuntimeError)

Testy jednostkowe

- Mozna testowac jak wczesniej, ale kiedy liczba testow rosnie, brak osobnego miejsca na testy i robi sie balagan.

Test::Unitto biblioteka Rubego do testow jednostkowych. Polegaja one na testowaniu kazdej indywidualnej jednostki funkcjonalnosci w programie lub systemie.Test::Unitudostepnia ustandaryzowany framework dla pisania i wykonywania testow.

# unit_testing.rb class String def titleize self.gsub(/(\A|\s)\w/) { |letter| letter.upcase } end end require 'test/unit' class TestTitleize < Test::Unit::TestCase def test_basic assert_equal("This Is A Test", "this is a test".titleize) assert_equal("Another Test 1234", "another test 1234".titleize) assert_equal("We're Testing", "We're testing".titleize) end end

Output:

Loaded suite unit_testing Started . Finished in 0.000407 seconds. 1 tests, 3 assertions, 0 failures, 0 errors, 0 skips Test run options: --seed 26015

| asserty | co porownuje |

|---|---|

assert(<boolean expression>) | |

assert_equal(expected, actual) | |

assert_not_equal(expected, actual) | |

assert_raise(exception_type, ..) { <code block> } | |

assert_nothing_raised(exception_type, ..) { } | |

assert_instance_of(class_expected, object) | |

flunk:flunk |

Benchmarki i profilowanie

Benchmarki

# simple_bench.rb require 'benchmark' puts Benchmark.measure { 10000.times { print "." } }

Output:

0.020000 0.010000 0.030000 ( 0.026244)

Kolumny to kolejno: user CPU time, system CPU time, total CPU, real time taken.

measureprzyjac moze rowniez blok kodu.- gdy pomiarow jest wiecej, poradzic sobie mozemy za pomoca metody

bm:

# multiple_bench.rb require 'benchmark' iterations = 1000000 Benchmark.bm do |bm| bm.report("for:") do for i in 1 .. iterations do x = i end end bm.report("times:") do iterations.times do |i| x = i end end end

Output:

user system total real for: 0.110000 0.000000 0.110000 ( 0.108295) times: 0.090000 0.000000 0.090000 ( 0.096391)

bmbm(10)przeprowadza test dziesięciokrotnie (w pewnych sytuacjach, CPU caching, memory caching i inne moga przeklamac wyniki).

Profilowanie

W Rubym profiler jest wbudowany. Jedyne co trzeba zrobic to umiescic require “profile” w kodzie, lub uruchomic go poleceniem ruby -r profile.

# profiling.rb require 'profile' class Calculator def self.count_to_large_number x = 0 100000.times { x += 1 } end def self.count_to_small_number x = 0 1000.times { x += 1 } end end Calculator.count_to_large_number Calculator.count_to_small_number

Output:

% cumulative self self total time seconds seconds calls ms/call ms/call name 100.00 0.18 0.18 2 90.00 90.00 Integer#times 0.00 0.18 0.00 1 0.00 0.00 Class#inherited 0.00 0.18 0.00 2 0.00 0.00 BasicObject#singleton_method_added 0.00 0.18 0.00 1 0.00 180.00 Calculator#count_to_large_number 0.00 0.18 0.00 1 0.00 0.00 Calculator#count_to_small_number 0.00 0.18 0.00 1 0.00 180.00 #toplevel

- W odroznieniu do benchmarkow, profiling powaznie obciaza szybkosc dzialania programu. Pomimo tego, spowolnienie jest spojne, a wyniki pewne.

- Pierwsza kolumna to procent czasu spedzonego w danej metodzie. Druga kolumna pokazuje ten sam parametr jako czas w sekundach. Trzecia to liczba wywolan danej metody.

- Aby profilowac tylko pewna czesc kodu, mozna skorzystac z biblioteki

profiler. Sekcje profilowana ustawiamy wtedy za pomoca polecenProfiler__.start_profileiProfiler__.stop_profile.Profiler__.print_profile($stdout)w odpowiednich miejscach.

Profilowanie Garbage Collectora

GC::Profiler.enable def factorial_iterative(n) (2 .. n - 1).each {|i| n *= i} n end m = 30_000 factorial_iterative(m) puts GC::Profiler.result

Output:

GC 176 invokes.

Index Invoke Time(sec) Use Size(byte) Total Size(byte) Total Object GC Time(ms)

1 0.035 179400 703480 17587 1.95800000000000151701

2 0.054 179400 703480 17587 1.37900000000001909939

3 0.071 179400 703480 17587 1.40599999999999059064

4 0.088 179400 703480 17587 1.25100000000000211031

5 0.104 179400 703480 17587 1.23499999999998610889

6 0.120 179400 703480 17587 1.21299999999999186251

7 0.136 179400 703480 17587 1.22200000000000086331

8 0.152 179400 703480 17587 1.15599999999999036859

9 0.168 179400 703480 17587 1.21299999999996410693

10 0.183 179400 703480 17587 1.19400000000002837197

[...]

Kilka przykładów optymalizacji

Hash a Array

#!/usr/bin/env ruby -wKU require 'benchmark' paragraph = %w[Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua Ut enim ad minim veniam quis nostrud exercitation ullamco laboris nisi ut aliquip ex ea commodo consequat Duis aute irure dolor in reprehenderit in voluptate velit esse cillum dolore eu fugiat nulla pariatur Excepteur sint occaecat cupidatat non proident sunt in culpa qui officia deserunt mollit anim id est laborum]*100 words_ary = [] words_hsh = {} Benchmark.bm(10) do |b| b.report("array") { paragraph.each {|word| words_ary << word unless words_ary.include?(word)} } b.report("uniq") {paragraph.uniq} b.report("hash") do paragraph.each {|word| words_hsh[word] = nil} words_hsh = words_hsh.keys end end

Output:

user system total real array 0.040000 0.000000 0.040000 ( 0.046044) uniq 0.010000 0.000000 0.010000 ( 0.002790) hash 0.000000 0.000000 0.000000 ( 0.005029) [Finished in 0.1s]

Powodem takich różnic jest fakt, że przy dodawaniu do tablicy, słowo musi być sprawdzone z każdym elementem tablicy. W przypadku słownika, nie jest to konieczne. Wygrywa metoda Array#uniq.

Lazy Instantiation

#!/usr/bin/env ruby -wKU require 'benchmark' class Employee def initialize @embezzled = [] end def embezzle(amount) @embezzled << amount end def embezzled_total @embezzled.inject(0) {|sum, amount| sum + amount} end end class FairEmployee def embezzle(amount) (@embezzled ||= []) << amount end def embezzled_total (@embezzled || []).inject(0) {|sum, amount| sum + amount} end end EMPLOYEES = 1000000 Benchmark.bmbm(15) do |b| b.report("empl") { EMPLOYEES.times {Employee.new} } b.report("fair") { EMPLOYEES.times {FairEmployee.new} } end

Output:

Rehearsal ---------------------------------------------------

empl 1.490000 0.000000 1.490000 ( 1.522579)

fair 0.960000 0.000000 0.960000 ( 0.971468)

------------------------------------------ total: 2.450000sec

user system total real

empl 1.460000 0.010000 1.470000 ( 1.489645)

fair 0.930000 0.000000 0.930000 ( 0.944282)

[Finished in 5.0s]

W pierwszym wypadku, dla każdego obiektu tworzymy pustą tablicę, zakładając, że każdy pracownik będzie nieuczciwy. W drugim przypadku, tablica tworzona jest tylko, gdy faktycznie coś zostało zapodziane - oszczędzamy więc pamięć i czas procesora. Gdy jednak wielu pracowników byłoby nieuczciwych, każde wywołanie metod embezzle i embezzled_total będzie wolniejsze z powodu dodatkowych warunków.

Ccccccbooooom!

#!/usr/bin/env ruby -wKU require "benchmark" require "inline" class Integer def count_set_bits(use_c = false) return csb(self) if use_c return 0 if self.zero? bits, x = 1, self bits += 1 while (x = x & (x - 1)).nonzero? bits end inline do |builder| builder.c "int csb(long x) { if (x == 0) return (x); int bits = 1; while ((x = x & (x - 1))) bits ++; return (bits); }" end end Benchmark.bmbm do |b| b.report("ruby") { 100_100.times { 152363.count_set_bits } } b.report("c") { 100_100.times { 152363.count_set_bits(true) } } end

Output:

Rehearsal ----------------------------------------

ruby 0.620000 0.000000 0.620000 ( 0.638407)

c 0.060000 0.000000 0.060000 ( 0.071187)

------------------------------- total: 0.680000sec

user system total real

ruby 0.610000 0.000000 0.610000 ( 0.655447)

c 0.070000 0.010000 0.080000 ( 0.079884)

[Finished in 1.9s]

Czasem po prostu jest szybciej. Dzięki RubyInline, możemy umieszczać kod C bezpośrednio w Rubym. Można też wywoływać funkcje C jakby były częścią Rubego.

Ogólnie

- Przy konstruowaniu złożonych warunków, na początku warto dać najszybszą metodę,

- Algorytmy iteracyjne szybsze są od rekurencyjnych.